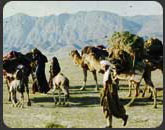

Pashtuns

In the minority in the North, Pashtuns sustain their traditional culture

in many ways, including song. One fascinating form unique to this people

is the landai (also spelled lundai or landey in English), whose form

is described this way by the Pashto writer Saduddin Shpoon:ìa non-rhymed

two-lined catalectic verse with five anapestic paeon feet, two in the

first line and three in the second, ending in MA or NA.î This pithy

poem reminds one of the Japanese haiku in its brevity and punch. Here

are two typical landai poems as translated by Shpoon:

Golaab che pre she bea raa shin she Zzre che Zakhmi she tol wojood

wer sara mrina

You cut a flower, and another grows, as red, as tender as the first.

This is not the way with hearts.

Pe loyo ghro de Khudaay nazar dai Pe sar-ye waawre warawi chaaper

goloona

God has an affair [literally: an eye] with lofty mountains; With snow

he caps them, and around them plants flowers.

Particularly among the nomadic Pashtuns, or kuchi, Shpoon estimates

that the overwhelming majority of the landai poems are composed by women,

who traditionally worked alongside men, unveiled.

One of my closest collaborators in trying to understand the music of

the North was Baba Naim, a Pashtun from Badakhshan, in the far-off mountains.

He came to Kabul, invited to join the Radio Afghanistan orchestra, where

he played the northern fiddle called ghichak.

He built a specially beautiful instrument with mother of pearl, sheep-bone,

and camel-bone inlay, and arranged to have one made for me, the only

examples of this type of instrument. Normally, the ghichak is made from

a standardized, multicolored spike with pegs, built in the crossroads

city of Tashqurghan, to which you only need to add wire strings, a wooden

bridge, and a nail as a prop to rest it on.

Baba Naim played regularly in the Spinzar Hotel in downtown Kabul for

foreign visitors, so appeared on a number of early recordings of Afghan

music in the 1960s and 1970s. I enjoyed his discourses on musical style

and tapped his broad repertoire, including a set of landai songs he

offered me. They are personal and unconventional, in terms of mainstream

Pashtun practice, showing influence from Badakkhshani practice, and

are very beautiful as sung to his plaintive ghichak.

By contrast, I taped some mainstream, southwestern Afghan music on

a short trip to Girishk and Lashkar Gah, beyond the largest Pashtun

city, Kandahar. One lively number they allowed me to tape was a song

for attan dancing, a pastime of Pashtun men. There are many variants

of the attan; estimates go up to thirty. Most of them share the common

feature of ring formation, in which all the men revolve in ever-increasing

agitation, hair flying to the rhythm. The tempo picks up until the last

man sinks to the ground in exhaustion. This recording, made indoors,

conveys only a fraction of the excitement that marks the attan, especially

since it happens at celebrations such as weddings, often prompting an

impromptu burst of enthusiastic gunfire as accompaniment. The text,

like many folksongs, references a particular locale, as translated by

Mr. Jehani, now working at the Voice of America in Washington, DC:

The girls of Spairwan (a village southwest of Kandahar) are dancing.

Their food is the green, sweet grapes, and the morning breeze touches

and caresses them. Beautiful girls who wear sandals, you drove the boys

crazy, So the other people cannot work and earn their livelihood.

|