Teahouse Music. Public performance is rare in the North, outside private parties. But in the towns, where men gather to trade goods and gossip on market days (once or twice a week, depending on town size), a couple of teahouses open their doors to musicians as well as customers. A single lute player or small ensemble play, mostly as background music, but sometimes as the main entertainment. They mix and match local and national songs and dance tunes, stringing them together in medleys heard above the clinking of teacups and the din of conversation.

Much of the music of the teahouse relies on a shared Uzbek-Tajik repertoire of tunes and texts. As neighbors since around 1500, and as the dominant population of the North, the Tajiks and Uzbeks have worked out a careful set of accommodations. Their contact spreads across a large geographic area, as the ethnographic map shows, on both sides of the Afghan border, and works out differently in each smaller region. Particularly in Turkestan and Kataghan, their neighborliness is noticeable. Each has adopted vocabulary, linguistic and musical, from the other. In the shared sound of the public teahouse performances, the texts combine the two languages seamlessly. Here's a quatrain, improvised in live performance, that practically alternates phrases between the two languages; the Uzbek is in italics, the Dari (Afghan Persian) in roman:

Samawarga ab-i jush

Bish afghani chainak gusht

Churtingni kharab qelma

Khoda uzi parda push

Boiling water in the samovar

Five afghanis for a teapot of meat

Don't worry;

God keeps our secrets

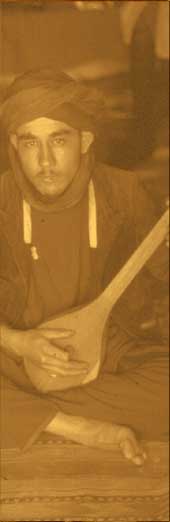

Uzbeks and Tajiks share a preference for the dambura, the most popular instrument. Though there are many long-necked, plucked lutes in this whole part of the world, they vary from place to place in structure and playing style. The northern Afghan dambura is the only one without frets (the little bars across the string that locate notes that you find on the guitar). This makes the instrument distinctive, pointing to a common aesthetic.

There are Tajik and Uzbek forms of the dambura, showing how ethnic boundaries work at various levels despite sharing across the lines. The Uzbek instrument is carved from three pieces of wood (mulberry or apricot):a, neck, joined to a belly, and a flat piece added as a lid. Its neck is pretty thick, and rounded at the back for easy holding. The Tajik dambura (called dumbrak in Tajikistan) is a graceful curve of just one piece, including neck and belly, to which the lid is added. It tends to be smaller, and the neck is peaked at the back to make it easy to play in the Tajik style, which features frequent use of putting one finger across both strings. Melodically, then, as we'll hear below, the typical tunes of Uzbeks and Tajiks are different, even as they use the same instrument that is typical only for their styles. Musicians know both tune types and playing techniques, even if they are not Uzbeks or Tajiks, like the fine performer Aq Pishak, a Turkmen.

In the teahouse, the two types of shared repertoire are the dambura tunes and the songs. Soundclips give examples of both. The solo dambura medley is played by Baba Qeran, universally regarded as the most venerable and knowledgeable damburachi. He starts with a naghma (tune) that people say is purely Uzbek. The old master carefully picks one string at a time, precisely marking off the danceable rhythm. Then he switches to a Radio Kabul popular song, strumming broadly across both strings. He rounds out the medley with an Uzbek song heard regionwide, "alpqadar tulari." Baba Qeran blends the tunes without losing a beat. His rock-steady rhythm and vast knowledge of tunes set him off as a master musician of the North.

Another way to gain a reputation might be to have a special "act" of your own, like Bangecha and his dancing dog. Abdullah "Buz-Baz" is named for his little marionette, a beautifully crafted figure of a mountain goat, which rests on a pivoting dowel connected by a string under a little stand to Abdullah's wrist. As he strums the dambura, the little goat pivots and rises, jingling slightly, as the filmclip shows. This buz-bazi trick is a way of making a little cash, but is also deeply tied to ancient beliefs about the power of mountain goats.

|